Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 56, No.2 - Summer 2010

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 56, No.2 - Summer 2010 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

The Siberian Architecture of Jurgis Mačiūnas

Stasys Goštautas

Abstract

This is the first essay

on George Maciunas and Fluxus in Lituanus. Of

all Lithuanian artists, Maciunas is not necessarily the best, but for

sure

the best known. Fluxus was born at the beginning of the sixties in New

York and Wiesbaden, Germany, where George was serving his military

duties. It slowly became a sensation as an iconoclastic movement

that wanted to destroy the commercialization of art. This essay deals

mainly with his architectural ambitions and his obsession with Siberia.

FLUXUS BERLIN NEWSLETTER, 2007-09-05

As unbelievable as it may sound, since so much has been said about Fluxus and Jurgis Mačiūnas (he spelled his name many ways, even using a Chinese variant, George Mao Chu Nas, but the version most commonly known to Americans is simply George Maciunas), one or two important facts about his life are usually left out, such as his architectural talent and his intent to build his Prefabricated Housing System in Siberia. I was astonished that of all the places in this world, he chose Siberia.

Then I found out that he was so obsessed with Siberia he had taken a series of courses on Russian history and even drawn maps to follow the Russian expansion across Siberia. To strengthen my point, between 1955 and 1960 George studied art history at New York University’s Art Institute, making instructive charts he planned to use as an art professor, andtook other courses in European and Siberian art as well. This spurred my curiosity, and when I inundated Google and Amazon with questions about Siberian art, I have to confess I found much more than I expected.

Mačiūnas’s

name was

little known in New York – as a

leader of a shaman movement, a bit of a revival of Dada, some

ready made objects à la Marcel Duchamp and ready-made

sounds by John Cage, the Zen teachings of Yoko Ono, happenings

by Allan Kaprow borrowed

from the Futurist Theater, and silent

films from Dali and Buñuel –

all this ephemeral, anarchistic mixture

he called Fluxus. Not too many

paid attention to a movement that

started off by denying everything

we consider art, and his iconoclastic

intention to destroy the commercialization

of art and build “Do It Yourself” [DIY] art that

preceded the twentieth century. To me, Fluxus was a game, and

George’s products were toys that you loved to play with and

then discard. I remember my first visit to his room (his apartment

was just a room), where he had invited us for a Fluxus

dinner. It was much as I expected from George: even such a

common event as dinner was an occasion to play, and instead

of a dinner, each one of us got one delicious Chinese dumpling,

or was it a Lithuanian dumpling known as koldūnas?

Mačiūnas’s

name was

little known in New York – as a

leader of a shaman movement, a bit of a revival of Dada, some

ready made objects à la Marcel Duchamp and ready-made

sounds by John Cage, the Zen teachings of Yoko Ono, happenings

by Allan Kaprow borrowed

from the Futurist Theater, and silent

films from Dali and Buñuel –

all this ephemeral, anarchistic mixture

he called Fluxus. Not too many

paid attention to a movement that

started off by denying everything

we consider art, and his iconoclastic

intention to destroy the commercialization

of art and build “Do It Yourself” [DIY] art that

preceded the twentieth century. To me, Fluxus was a game, and

George’s products were toys that you loved to play with and

then discard. I remember my first visit to his room (his apartment

was just a room), where he had invited us for a Fluxus

dinner. It was much as I expected from George: even such a

common event as dinner was an occasion to play, and instead

of a dinner, each one of us got one delicious Chinese dumpling,

or was it a Lithuanian dumpling known as koldūnas?

In January 1965, when Mačiūnas was just starting the Fluxus movement, the Guggenheim held an art exhibit called “Eleven from the Reuben Gallery,” with many artists who, one way or another, became connected to Fluxus. From the eleven artists, we easily recognize George Brecht, Allan Kaprow, and Claes Oldenburg, – all known for pop art and happenings, all under the strong influence of John Cage, and all future Fluxus members, but no George, who was not part of the Guggenheim exhibit.

Thanks to Jonas Mekas, his buddy, Fluxus suddenly became important and relevant, especially in his home country Lithuania, where for whatever reasons, the Guggenheim and the Hermitage State Museum at St. Petersburg chose Vilnius as the capital for their next experiment, a branch to house Mačiūnas and Mekas’s bizarre collection. Despite the honor of being “seduced” by two outstanding museums of the world, Lithuania’s intelligentsia rebelled against the idea and did everything in their power to sabotage the project. To my understanding, the idea deserves our attention, and there could be some advantage from the cooperation between local, provincial, and world-class museums. Lithuania would be the first postcolonial ex-Soviet country to take part in an interesting experiment in the name of globalization, where art by Mačiūnas and Mekas would find a final resting place. I wonder what George, the charismatic “Chairman” of Fluxus, would say if he knew that his artifacts and toys were going to be part of a museum with the prestigious Guggenheim and Hermitage labels.

It is not clear who is getting the best of the deal, and that is one reason why many oppose this project, in spite of the fact that Artūras Zuokas, the former mayor of Vilnius and a shrewd politician, put his prestige and career on the line for it. In 2009 after all, Vilnius was the European Union’s Capital of Culture, and that honor does have certain obligations, such as, perhaps, building a global museum. Vilnius has just opened a huge museum called the “National Gallery of Art” with twelve galleries and no space dedicated to Mačiūnas or Mekas. So, another museum next to the River Neris would seem appropriate.

We all know the success of the Bilbao Guggenheim [1997] and the disaster of SoHo [1992-2001]. Lithuania is concerned more than anything else with the question of whether this huge investment is worth making at all. We are talking about 300 million litas, which comes to approximately 120 million dollars, not a small sum for a country in economic crisis. Of course, it would still take some ten years to build, even if there were national consensus. After all, other plans for branches in such places as Salzburg, Guadalajara, Rio de Janeiro, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, have failed to materialize. I am not sure how far the project in Abu Dhabi, the largest of all Guggenheim satellites which is scheduled to be opened in 2012, has progressed.

Zuokas helped to open an art gallery in downtown Vilnius, located behind the National Library and the Parliament, called the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center, or just J/M/V/A/C. In my few days in the capital, I saw a diploma exhibit by a young student, Dainius Meškauskas, with the title “Radijo Tyla FM (101,5:108,0) MHz,” with sixty-six radios, each one playing a different FM station. Dainius said he was inspired by one of 39 my first Fluxus friends, Nam June Paik, but the idea of total music probably came from John Cage. At any rate, this gallery is giving a young artist a great opportunity to exhibit the lastest in avant-garde work. The Mekas Center has already published a book in two languages, The Avant-garde From Futurism to Fluxus (2007), which, very humble in its presentation, is an impressive collection of Fluxus documents and has a chapter devoted to architecture. Too bad the first chapter, devoted to the avantgarde poet Kazys Binkis, is marred with errors. I would have preferred to see a poetry analysis from Jonas Mekas instead.

To many Lithuanians, George was a Bolshevik sympathizer, even though he fled the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1944. He admired the Communist philosophy – should we call it that? – and was determined to mass produce art: ephemeral, anonymous, art destroyed by fire, art that belonged to everybody, with no name and no property attached; so ephemeral that nobody would want to own it. That is Fluxus – humorous, spontaneous and economic – most of its objects, like match boxes or hand printed posters, were made of inexpensive materials.

I first met George in 1964, after I

joined the Latin American

desk of UPI, where my desk neighbor, Helen Thomas, used

to pass me books that she got for review. As a pastime, I was

writing cultural echoes of art life in New York City for Latin

American newspapers and a Lithuanian daily in Chicago. I

happened to meet Mekas,whose poetry I loved, in the

Filmmakers’

Cinematheque, where I went to see samples of the

New America Cinema. After the show, when I saw a young

professional – looking out of place – sweeping the

floor of the

theater at 80 Wooster Street in Soho. I asked him why he was

doing it. He answered that he was helping the Mekas brothers,

Jonas and Adolfas, to keep the place clean at no cost to

them, “but I am not a regular janitor here, I am an

architect, my

Prefabricated Housing System is being built in Siberia.”

Astonished,

I asked why, of all the places in the world, Siberia? I don’t

remember his exact answer, but

to him Siberia did not sound

like the infamous Gulag; rather

it was a marvelous, yet-to-bediscovered

continent where the

future was being built. “I am

writing,” he added, “to Nikita

Khrushchev, offering my services.”

I was appalled: no wonder the New York Lithuanian community

called him a “Commie.” A friend of

Mačiūnas’s, Henry

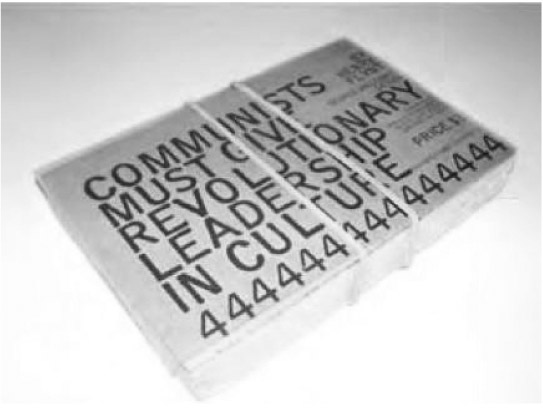

Flynt, published a strange pamphlet, entitled Communists Must

Give Revolutionary Leadership in Culture (1965), which I

had not

yet seen, but George never stopped talking about the

piece, which was supposed to evaluate contemporary

architecture,

music, the visual arts, and film. I do not remember how much

I agreed with Mačiūnas’s remarks, but I wanted to find out

more about those architectural structures designed for Siberia.

Finally, I found them; or rather I found the drawings and an

architectural model built many years later for the Maya Stendhal

Gallery for an exhibit held in August 2008. At present, two

students from Latin America, Maria Carolina Carrasco of Chile

and the Mexican Cuauhtémoc Medina González, are

working

on PhD dissertations about Mačiūnas and Fluxus. Carrasco is

researching Mačiūnas’s architectural venture for her thesis

at

New York University’s Art Institute and has already written

one study for the above-mentioned book. Medina González is

finishing her dissertation on Fluxus nonart and antiart at the

University of Essex.

which I

had not

yet seen, but George never stopped talking about the

piece, which was supposed to evaluate contemporary

architecture,

music, the visual arts, and film. I do not remember how much

I agreed with Mačiūnas’s remarks, but I wanted to find out

more about those architectural structures designed for Siberia.

Finally, I found them; or rather I found the drawings and an

architectural model built many years later for the Maya Stendhal

Gallery for an exhibit held in August 2008. At present, two

students from Latin America, Maria Carolina Carrasco of Chile

and the Mexican Cuauhtémoc Medina González, are

working

on PhD dissertations about Mačiūnas and Fluxus. Carrasco is

researching Mačiūnas’s architectural venture for her thesis

at

New York University’s Art Institute and has already written

one study for the above-mentioned book. Medina González is

finishing her dissertation on Fluxus nonart and antiart at the

University of Essex.

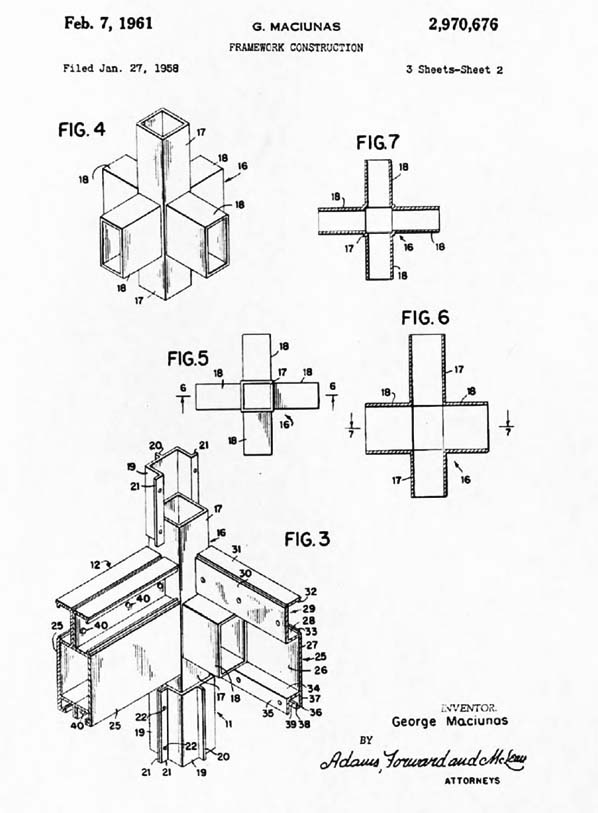

Mačiūnas was a serious architect, graduating from Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh with a bachelor’s degree in Architecture in only two years. In the late fifties and early sixties, he joined Knoll and Skidmore, then Owings & Merrill, as an architect.

But to find a direct relation between his architecture and Siberia is another matter, and I think his construction ideas would fit many other places of the world just as well. But for George, Siberia was an obsession, and there is almost no letter or piece of writing of his that does not mention it. So, his architectural project was a natural evolution from his interest in Siberia. He disliked modern architecture and such icons as Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, whom he called “frauds.” Contrary to Wright, who sought an organic architecture, Mačiūnas went after the “ineffable space” of a Le Corbusier.

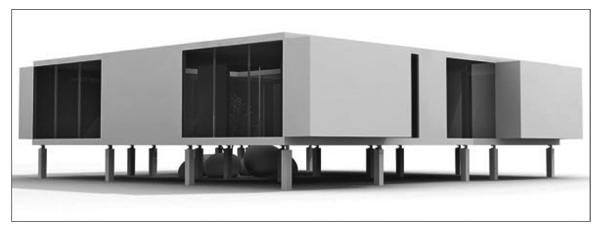

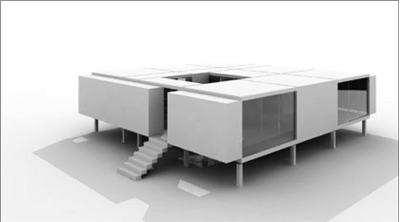

He admired the architecture of the Soviet Union that had invaded the cityscapes of Lithuania. But he thought that his buildings were even more efficient than the Soviets’ and that Siberia should accept his plastic housing design, which he called the Prefabricated Housing System. With plastic, a fast assembly line, and, of course, no need for heavy equipment, the prefab units could be erected using local untrained labor, whether in Siberia or the Amazon, almost a Do It Yourself [DIY] system. Mačiūnas got as far as explaining and drawing each part of the building through charts, diagrams, and isometric cross-sections. Certainly, Mačiūnas’s Prefabricated Housing System was economical and efficient; for in the sixties he had already previewed a house heated by solar power.

Illustrations provided courtesy of The George Maciunas Foundation, Inc. and Standahl Gallery of New York.

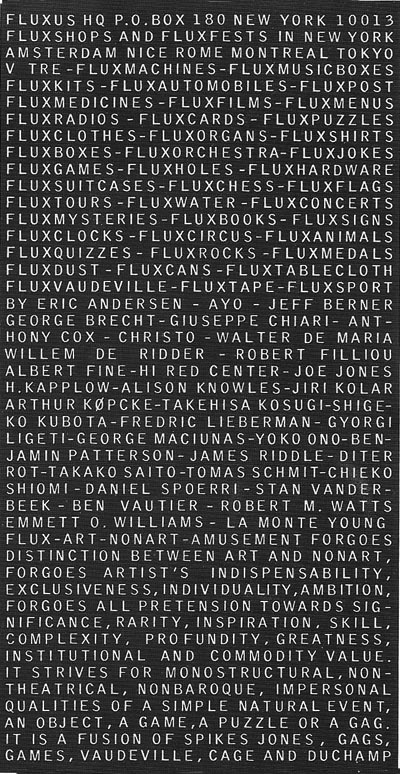

Jurgis Mačiūnas, Fluxus

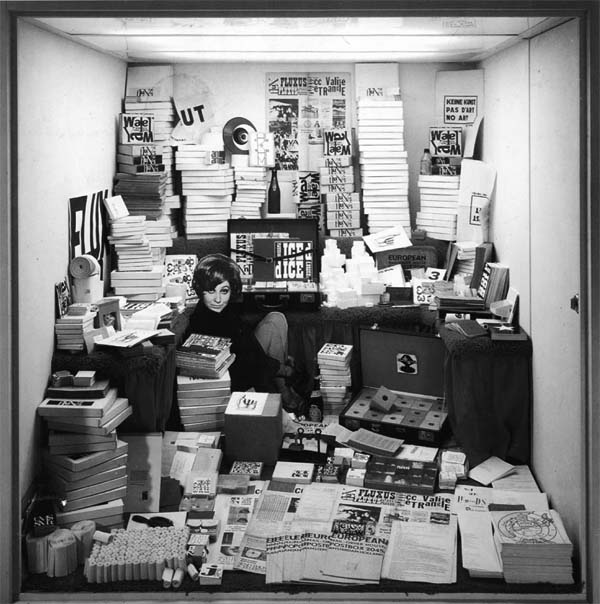

Willem de Rider. European Mail-Order Warehouse/Fluxushop.

Silverman

Fluxus Collection at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas.

Patent application for Maciunas’ Framework

Construction

Mačiūnas’s

Prefabricated Building System Architectural Model:

142 x 147

x 40.5 cm. 162.5 x 167.5 cm base.

Heavy density fiberboard with styrene,

extruded aluminum, acrylic panels, and wood base.